Phone: +86-755-2357-1819 Mobile: +86-185-7640-5228 Email: sales@ominipcba.com whatsapp: +8618576405228

Optical PCB & Silicon Photonics: The Future of High-Speed Interconnects

Break the bandwidth bottleneck. Analyze the integration of Silicon Photonics with printed circuit boards, covering embedded waveguides, CPO assembly, and sub-micron manufacturing challenges.

PCB TECHNOLOGYPCB MANUFACTURINGPCB ASSEMBLY

OminiPCBA

1/1/20267 min read

Not long ago, copper paths carried signals just fine - now they struggle to keep up. Hitting walls at 224 Gbps per lane, these tiny pathways heat up instead of transmitting cleanly. Data centers push harder, machines crave more, yet the metal resists faster flows. Even short runs on circuit boards weaken signals too much. Boosting them back means burning extra power, which leads nowhere good. Petabit hunger grows, but copper cannot feed it.

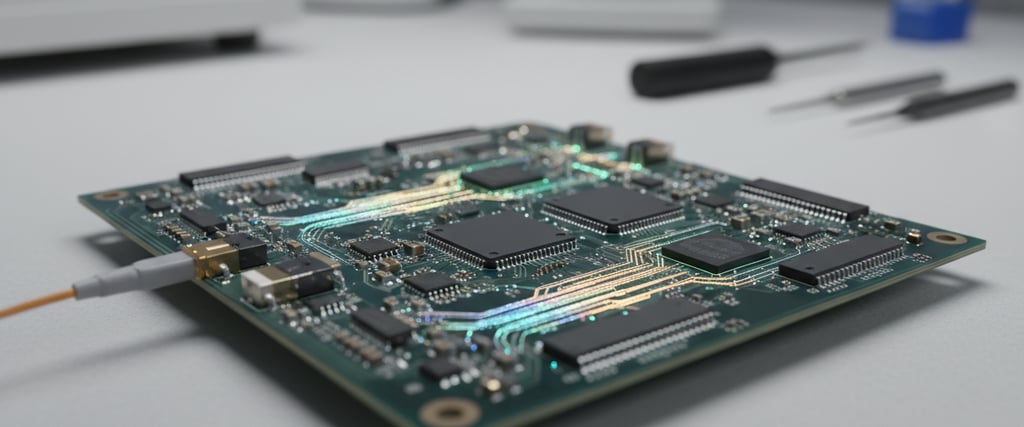

Now comes the Electro-Optical Circuit Board, born where physics draws its line. Instead of just changing wires, engineers weave Silicon Photonics straight into the board's core. Light moves data across chips - no drag, no warmth left behind. While electric currents fade and warm up circuits, beams stay clean and cool. That change pulls old-school circuit making into new territory: aligning lasers, shaping tiny glass paths, sealing fragile waveguides beside silicon. What once lived in labs now fits inside everyday devices.

The Copper Wall Physics

Figuring out why Optical PCBs matter starts by measuring how badly electrical signals fail. A copper trace only handles so much bandwidth over distance. Just past 10 inches on top-tier Megtron 7 material, an 112G PAM4 signal fades into noise at the receiver. Signal clarity vanishes fast under such loss. Instead of pushing further, engineers turn to retimers - chips that rebuild the waveform but sip more power.

Unlike copper paths on circuit boards, light-carrying channels built into the board lose only about 0.05 dB every centimeter - far less loss when running at high speeds. Because they carry data with light instead of electricity, these links ignore magnetic noise and won’t interfere with neighbors. Packed tightly together, they skip the empty spaces or shielding lines that metal wires need to stay clean. Moving large amounts of information using optics isn't just better - it's required if we want each bit to use barely any power. Energy simply can’t escape heat buildup unless connections switch from electrons to photons.

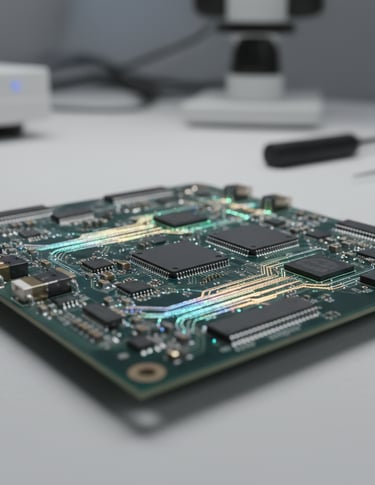

Optical PCB Structure

A circuit board using optics isn’t just a regular one fitted with fiber links. Instead, it holds built-in pathways for light, tucked inside its layers like hidden trails. These channels steer photons much like wires move electricity, only without metal. They act as connections made of pure guidance, moving signals through thin transparent routes where traditional traces would be

Polymer vs. Glass Waveguides

What you pick for a waveguide shapes how it gets made. Because they fit well with existing steps, plastics lead when putting waveguides on boards. A spin or lamination step puts those materials down on the base layer, then light-based etching carves the design - much like handling classic photo coatings. Still, survival matters: each run through typical soldering heat, up to 260°C, can’t break them.

Tiny glass pathways inside super thin layers give sharp light signals, nearly losing nothing along the way. Still, fitting these brittle panes into flexible circuit bundles brings tough physical problems. Heat changes make the glass and plastic parts swell at different speeds. That uneven stretch may split them apart when temperatures shift too much.

Co-Packaged Optics As System Enabler

Co-Packaged Optics pushes the move toward Optical PCBs. Instead of sitting on the board's edge like a QSFP-DD, the optical part now lives closer to the core. Electrical links used to stretch from ASIC all the way across the board - now that distance causes issues. That extended run limits speed, creating a choke point in older setups.

Right next to the ASIC sits the optical engine now - sometimes built right into the same base layer. Much shorter electrical paths mean less energy gets burned off. Because of this shift, circuit boards must guide light as well as electricity. Instead of loose fiber tails coming out of a module, thin pathways inside the material carry the signals. Manufacturing teams face materials that behave differently, mixing light and current in ways older systems never did.

The Alignment Challenge With Sub Micron Precision

Every so often, electricity forgives small mistakes. Misplace a part by fifty millionths of a meter, yet heat and pull can fix it mid-process - surface forces nudge things right. Light does not play that way. Shine through glass built for single-mode travel, where nine-millionths of a meter wide is standard, then expect zero mercy. Getting energy from laser to path demands near perfection - one half to one whole micron precision - or lose everything. Physics here allows no second chances.

A typical pick-and-place tool in standard turnkey PCBA setups works within 10–20 micron accuracy. Because of that margin, an entirely different build setup becomes necessary. Some top-tier production sites now use what's called Active Alignment technology. Instead of relying only on static camera guidance, these systems switch on the laser while placing it. They track how much light comes through during positioning. Movement happens across six directions at once - up-down, left-right, forward-backward, tilt, yaw, roll - all adjusted by the machine. Once peak signal transfer shows up, ultraviolet light hardens the glue almost instantly.

Looking at numbers from top companies, like the ones Omnicpcba studied, shows moving from passive to active alignment might boost connection performance by 3dB - which means twice as much usable light signal. A change like that quietly reshapes what systems can do without needing more parts. Results of real-world tests suggest small tweaks in setup bring big gains in output. Not every design uses it yet, though the difference is hard to ignore when matching fibers. Some teams still stick with older methods simply because switching takes effort. Yet even cautious adopters notice how little extra work delivers noticeable improvement. When signals travel through glass strands, tiny adjustments matter far more than expected.

Optical Vias and Turning Mirrors

Light bends hard when changing direction. Electrons shift paths without much trouble, yet beams of light resist sharp turns. Sending optical signals from flat pathways up toward components standing upright needs a precise redirection. A ninety degree pivot becomes necessary for proper alignment between layers. Tiny mirrors set at forty five degrees get built right into the guiding structure. These angled surfaces catch incoming rays, then bounce them straight upward where needed. Each mirror acts like a redirector placed exactly where path changes occur.

Starting with sharp tools or lasers ensures clean cuts when shaping the mirrors. Rough spots on the surface send light in random directions, which drains efficiency. To bounce back more light, a coat of gold or aluminum gets applied. That coating step slips in between layers during assembly, making the build harder to manage. When pressure builds inside the laminating machine, those mirrors must hold their shape - or everything fails. If resin moves too much, it bends the mirror’s form, breaking the line of sight needed for function.

Keeping Photonic Engines Cool

Funny thing about light signals - they don’t warm things up. Still, the tiny lasers making the glow react badly when it gets too hot or cold. Light color shifts as temperature changes, even if just a little. That shift can miss the target slot in a WDM filter. Once it slips past that gap, everything stops working.

Cooling an optical PCB demands unusual methods. Instead of relying on air movement, the photonic engine needs metal-to-metal contact with the frame. Copper inserts or active cooling modules get built right beneath the light source. Yet those cooling modules draw electricity themselves. Newer CPO setups aim to remove such parts by adopting lasers that work without chilling. That shift pushes greater demand onto the board's skill at moving warmth through material alone.

Cleanliness Redefines Manufacturing Standards

A speck of dust usually means trouble in regular electronics work, especially when that bit conducts electricity - it could trigger a short. But inside an optical setup, even non-conducting bits act like giant rocks sitting right where light needs to pass through. Imagine one tiny grain, just five microns wide, parked on a waveguide surface - suddenly ten decibels vanish, enough to wipe out the entire signal. Light doesn’t get second chances.

Now cleanliness in optical PCB work matches what chip makers demand - think Class 100 or even Class 1000 spaces. Instead of only washing away leftover flux, workers now rely on plasma treatments to wipe out invisible organic gunk right down to molecules prior to joining parts. At Ominipcba, old-style rinsing rarely cuts it for lens-facing surfaces - so teams turn to CO2 snow sprays or vapor baths made with solvents to leave those zones perfectly clear.

Reliability and How Materials Age Over Time

Over years of use, optical polymers slowly lose their clarity. While copper stays steady, these materials react under strong light or UV exposure. Light damage tints them yellow, a shift that builds up silently. That tint pulls in more light than intended. Performance slips bit by bit as the material changes. Shelf life begins the moment they are made.

Moisture gets pulled into polymers over time. Inside the waveguide, those water bits soak up light signals meant for telecom wavelengths - like 1310nm or 1550nm. Because of this, Optical PCBs either need airtight enclosures or have to be built using fluorinated plastics that resist water. Testing their durability doesn’t stop at heat changes anymore. Now it also involves long runs under high heat while tracking how much light still passes through. A drop means the material is breaking down.

Rework Leads to More Rework While Yield Suffers

That one flaw might trash the whole board could be the biggest money problem in making optical PCBs. Usually, fixing a broken part on a regular circuit means heating it off and putting a new one. With light-based circuits though, parts stick using glue that locks tight under ultraviolet light. When something like an optical sender sits even slightly crooked, tossing out everything becomes the only option. A single mistake may mean losing a board valued at many thousands.

Not chasing fixes later means getting things right much earlier. Quality checks happen first, not last - every single waveguide inspected by OTDR before it even enters assembly. Die attachment follows tight rules, no exceptions allowed. Testing the optical part on its own, separate from everything else, is becoming standard practice across factories now.

The Photonic Future

A shift unfolds when silicon light tech meets circuit boards - not merely progress, but a joining of separate worlds: printing methods, chip making, light systems. This blend hints at times ahead where data flow feels endless, delays shrinking to nothing more than how fast photons travel.

Still, making this happen means learning fresh challenges. Getting it right needs circuit board builders to adopt the accuracy found in light labs along with the spotless conditions of chip factories. With copper's limits becoming harder to ignore, producing hybrid electronic-light systems will separate real pioneers from old-school manufacturers - opening doors for advanced supercomputing ahead.

Contacts

Email: sales@ominipcba.com

Mobile: +86-185-7640-5228

Copyright © 2007-2026. Omini Electronics Limited. All rights reserved.

Head Office: +86-755-2357-1819

Services

Your China turnkey partner for electronics manufacturing. We bridge design to delivery by leveraging the Shenzhen electronics ecosystem for precision engineering and streamlined PCBA supply chain logistics.

Ready to Build?

Get a comprehensive quote within 24 hours.