Phone: +86-755-2357-1819 Mobile: +86-185-7640-5228 Email: sales@ominipcba.com whatsapp: +8618576405228

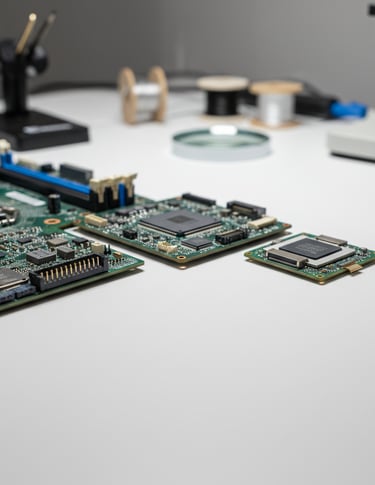

Mastering PCB Miniaturization: HDI, mSAP & 008004 Assembly Design

Overcome the physical limits of high-density interconnects. Analyze the fabrication and SMT challenges of 008004 components, mSAP traces, and ELIC stacking.

PCB TECHNOLOGYPCB MANUFACTURINGPCB ASSEMBLY

OminiPCBA

1/1/20266 min read

Out of nowhere, today's gadgets need to be tinier while doing more work. Because of that pressure, circuit boards have stopped being flat platforms for parts and turned into intricate 3D networks. Shrinking down now demands packing more function into every tiny space. Engineers can’t rely on old habits anymore. Instead of assuming distance prevents problems, they face challenges where materials, physical laws, and production limits meet under microscopes.

Nowhere is the line clearer between chip packaging and circuit boards - they blend. Features once only on silicon now shape designs, bringing manufacturing down to fractions of a micron. Every part of the signal path needs fresh eyes: how copper grains form, even how solder paste flows when joined.

The Geometry Of The Trace Reaching Beyond Thirty Microns

Tiny circuits once got made by washing away extra copper. A protective layer stayed put while chemicals ate bare metal around it. When lines shrink near 40 millionths of a meter, though, that method starts failing. Liquid acid spreads sideways during removal, not just down. That sideways bite leaves traces wider at the base than top. Such uneven shapes narrow usable conduction space, raising electrical resistance and disrupting signal consistency.

Getting circuits small enough for future wearables and medical devices means shifting to modified semi-additive processes. Rather than cutting away metal, this technique builds up the wiring bit by bit. First comes an ultra-thin conductive base laid on top of insulating material. Then a light-sensitive coating goes on, shaped to leave gaps where wires should form. Through those openings, copper fills in via electric current. The result? Tightly packed lines stand almost straight up, with flat sides like tiny rails - down to 20 micrometers wide - and stable electrical performance throughout.

Though mSAP needs unique design guidelines, its fine traces stick through both physical grip and molecular bonding. Because bond strength drops below standard foil levels, fixing mistakes risks damage. Shaping pads carefully spreads out strain when temperatures swing. That care helps avoid cracks forming under pads during heat shifts.

The Component Scale 008004 Reality

Downsizing keeps pushing limits in passive components - first 0402, then 0201 crept in, followed by 01005 slipping through. Now 008004 parts, tiny at just 0.25mm by 0.125mm, are entering production lines. So small they vanish under normal sight, these capacitors resemble specks more than electronics. Spot one on a plant surface and you might brush it off without knowing. Their size fools even trained eyes into missing what's right there.

Putting these parts together in a ready-to-go circuit board assembly line brings tough problems for the soldering method. What causes most trouble? Surface tension does. When heated, melted solder pushes around - uneven warmth might twist the part sideways or yank it right off its spot. Designing the holes in the metal sheet turns into a game of managing how goo flows. How much paste lands matters down to the tiniest bit - skimp on it and the connection fails, add just a hair too much and it spills across gaps narrower than a human hair.

Tiny holes in stencils make printing tricky when using regular Type 4 solder powder - it just does not fit well. Because of this, many makers now choose finer powders like Type 5 or even Type 6, where grains are between five and fifteen micrometers wide. These smaller particles flow better during application. Without them, paste might stick instead of releasing cleanly. On top of that, the metal sheet benefits from a slick nano-layer that keeps flux from clinging. That layer helps keep openings clear, especially after dozens of prints back to back.

Z Axis Integration Using ELIC and Stacked Microvias

Up becomes the next option once the X-Y plane fills up. Instead of spreading wide, connections start stacking tall. Regular through-hole vias take up too much space, cutting through all layers even when not needed. A smarter path appears with Every Layer Interconnect, sometimes called Any-Layer HDI. This method links layers without wasting room.

Stacking tiny holes filled with copper right on top of each other is possible with ELIC. These form a continuous column cutting through the whole board - or ending partway. Because of this, routing paths move freely across layers without needing extra space for branching traces. Staggered designs lose their hold here. The circuit board begins to behave more like a dense web of connections than separate levels.

Still, piled-up microvias bring mechanical stress into play. Where one via meets the capped top of another beneath, weakness shows up. Heat during reflow makes the insulating layer stretch vertically, tugging at that spot. Without tight control over plating steps - especially blocking oxygen exposure - the bond might split apart. Testing these layered circuits isn’t just about checking if power flows; shifts in resistance under sudden temperature swings reveal tiny cracks forming.

3D Space Use with Rigid Flex Designs

It isn’t just shrinking parts - it’s shaping circuits to match curved spaces. Where old designs used clunky plugs and tangled wires, rigid-flex boards merge connections right into the material. Folding becomes possible because the wiring bends with the board, tucking neatly beside power cells, detectors, or case edges.

Getting rigid-flex right means knowing how materials behave under pressure. Stress on bends stays lowest when conductive layers sit dead-center in the flex layer sandwich, according to neutral bend axis principles. Where stiff FR4 joins flexible polyimide, forces pile up sharply. To keep copper traces from snapping there, engineers often wrap edges like a bikini coverlay or add thick epoxy patches for support.

A wobble here, a bend there - rigid-flex boards misbehave on assembly lines. Not stiff like regular ones, they droop without support. Because of their shape, custom trays must hold them level through each step. When the flexible part sags mid-print, paste lands unevenly across pads. Uneven layers mean connections fail more often down the line.

Heat Control in Small Spaces

Heat builds up faster when components pack tighter together. Squeezing powerful chips and power regulators into tiny spaces leads to pockets of intense warmth. These warm zones might slow down operation or harm delicate battery materials. Standard cooling fins usually take up too much room in compact gadgets.

Heat moves best when the circuit board acts like a cooler. To make that happen, tiny holes filled with copper go right into the spots where power parts sit - this method has a name, VIPPO. Those metal-lined paths carry warmth down to inner layers connected to ground. But there’s a catch with VIPPO: if the surface isn’t completely flat, the part might wobble while being attached. What makes things worse, air trapped inside the filled holes can escape during heating, leaving gaps in the connection that slow heat flow.

Solid copper pieces sometimes get built right into circuit boards beneath the warmest spots to help things last longer. Because it works well, but makes pressing layers together trickier - the goo needs to move around the chunk of metal without gaps forming. The folks at Ominipcba frequently work alongside design experts to model how the liquid spreads when squeezed, making sure insulation wraps completely around those dense inserts.

Signal Behavior in Crowded Environments

Miniaturization fights a hidden foe: crosstalk. Packing traces tighter means saving room - but brings them into closer electromagnetic contact. In fast digital circuits, interference grows until signals blur beyond recognition.

Getting around this issue without widening gaps means using slimmer insulating layers so the return path sits nearer the signal line. That boosts how tightly it connects capacitively to ground, overshadowing crosstalk from neighboring lines and keeping energy focused where needed. Yet, these thin insulation sheets can be tricky to work with when building boards, plus they risk failing high-voltage tests due to weaker breakdown resistance.

Over thin lines, the fiber weave issue stands out more. When a slim high-speed path crosses straight above a glass cluster in the material, its electrical environment shifts compared to one passing over a resin-heavy space. That mismatch leads to timing differences. To balance such inconsistencies, shrinking designs require evenly dispersed glass weaves or rotated layout patterns. Shrinking circuits push these adjustments into necessity.

Testing the Untestable

Validation stands as the last barrier when shrinking devices. Instead of using standard "bed of nails" testing, which needs pads between 0.5mm and 0.8mm wide, engineers face tight space limits. When each micron matters, making room for those test spots feels like wasting precious ground. Yet skipping them isn’t really an option either.

Now machines check circuits without needing pads. Instead of physical contact points, they rely on built-in chip features like JTAG to confirm solder links work. Tiny probes still handle power and ground checks, moving carefully across boards. These arms take their time, making each run longer than automated methods. Speed suffers because precision demands patience.

Eyes alone can’t catch every flaw these days. Solder paste gets checked by machines that map its shape in three dimensions. Components sit at certain heights - those get measured too - to guess how solid their connections are. When tiny balls hide underneath a package, like with BGAs or CSPs, regular views fail completely. Only sharp 3D X-ray images reveal what lies beneath those closed spaces. Cracks where metal refuses to bond show up clearly through computed tomography. Air pockets inside joints? That kind of problem needs deep scanning to spot. Peeling things apart just to look is no longer required when imaging works so well.

The Meeting of Different Fields

Nowadays, shrinking circuit boards isn’t just one step after another. Picture an electrical engineer passing sketches to a layout person, who then ships off Gerber files - those days are gone. Instead, everything moves together, at once. Equipment that places parts on boards shapes how those parts get picked. The way layers bond under heat and pressure sets hard rules for layer arrangement. Decisions fold into each other, back and forth, without waiting.

As we push toward 008004 passives and 15µm trace widths, the successful realization of a product depends on the tightness of the feedback loop between design and manufacturing. It is a discipline where the smallest details - a micron of solder mask, a grain of copper, a degree of thermal profile - wield the greatest influence over the final success of the product.

Contacts

Email: sales@ominipcba.com

Mobile: +86-185-7640-5228

Copyright © 2007-2026. Omini Electronics Limited. All rights reserved.

Head Office: +86-755-2357-1819

Services

Your China turnkey partner for electronics manufacturing. We bridge design to delivery by leveraging the Shenzhen electronics ecosystem for precision engineering and streamlined PCBA supply chain logistics.

Ready to Build?

Get a comprehensive quote within 24 hours.